JavaScript: Not your father's inheritance model - Part 1

This particular chapter is further divided in two parts. Read Part 2.

In a previous installment in this series we saw how we could create constructor functions in JavaScript. Back then I just mentioned that we don't have classes in JavaScript and that there's this weird prototype property in every object.

Let's dig into those concepts a little more and try to understand how inheritance is achieved in JavaScript.

Inheritance as we often know it

For myself and probably the majority of you reading this blog, inheritance in an Object Oriented programming language is directly associated with the concept of classes.

When we work with C#, VB, Java, Ruby, and many other popular programming languages, each of our objects is of some type, which is represented by a class. Our objects automatically inherit functionality from their associated class often called base or super class, and any other classes that the base class itself is associated with (i.e. derives from.)

That's nothing new to you, I'm sure. I'm just re-hashing that in the previous paragraph to make a comparison later. Let's call this model class-based inheritance.

That's not the end of the story

This may come as a surprise to some people, but class-based inheritance is not the only way to obtain Object Oriented inheritance (by saying Object Oriented I automatically excluded those of you that thought Copy/Paste Inheritance was one of them.)

It just so happens that the JavaScript language designers chose another inheritance model. And they are not alone in that choice. By opting for a prototype-based inheritance model , JavaScript joined the ranks of other programming languages such as Self , Lua , and Agora.

The prototype is the king

Objects in JavaScript don't inherit from classes; they inherit straight from other objects. The object they inherit from is called their Prototype (I'm using a capital P here to avoid confusion down the line.) The object's Prototype is assigned right at construction time.

You may be intrigued and say: But when I create my objects I don't remember specifying any Prototype stuff. What gives?

Let's see what happens then. When you create a plain Object using either of the following syntaxes

var obj1 = new Object();

obj1.name = 'box'

//or

var obj2 = { name: 'door' };

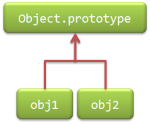

JavaScript will automatically assign a Prototype to each of these objects. This prototype will be Object.prototype.

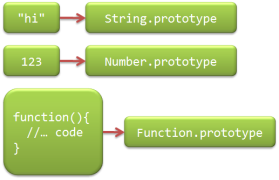

Similarly, let's see what happens with a few of the other object types in JavaScript.

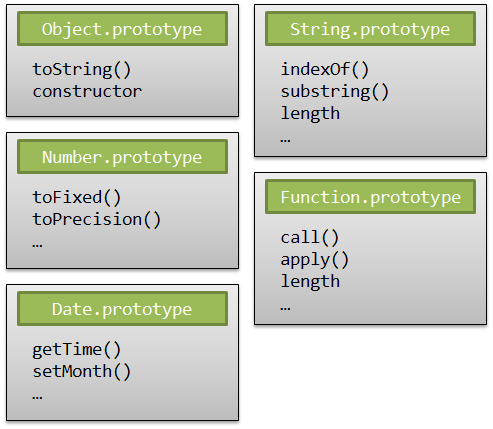

The Prototype objects is how every object in JavaScript is born with inherited functionality. For example, the substring() method that every String object has is a method defined in the object String.Prototype.

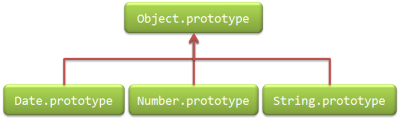

The prototype objects themselves also inherit from Object.prototype, that's how every object of any type has a toString() method.

When you try to access 1234.constructor, as an example, the runtime will look for a constructor property on our object (the number 1234). It doesn't have one so the next step taken is to check if that object's Prototype has it. The Prototype for 1234 is Number.prototype and it doesn't have that property either. The runtime then looks on the Prototype of Number.prototype, which is Object.prototype. That last object does have a constructor property, so that is returned. If it didn't, undefined would have been returned instead.

In Part 2 we will see how to create our own Prototypes.